Civilizations Clashing

Book reviewed: Russia and Europe by Nikolai Danilevsky

In the 1990s, Samuel Huntington published his famous The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, an expanded version of an article he’d originally penned for Foreign Affairs. The book was a necessary corrective to the exuberantly optimistic view that had set in after the collapse of the Soviet Union, best exemplified by Fukuyama’s “end of history” paradigm. The Pollyannas pointed to a bright new dawn unfolding: the Red Empire was gone, the gargoyles of totalitarianism had been vanquished, and (neo)liberalism could spread around the world untrammeled. The world had changed; man had fulfilled his destiny. For Huntington, this was an illusion. Far from being over, history would continue; only the nature of conflicts would be different. Unlike the national and ideological fighting that defined much of the 20th century, the future battle lines would be drawn along civilizational fault lines. Huntington argued that, as all civilizations were different, each one possessed its own unique trajectory, and so, pace the claims of West-centric utopists and neoliberal hawks, Western civilization, for all its indisputable advantages, could never be universal.

However persuasive, Huntington’s arguments were far from original. More than a hundred years before, Nikolai Danilevsky, godfather of Russia’s Slavophile movement, advanced a similar conception of the world in Russia and Europe (1869). Though Danilevsky is considered to have anticipated the ideas of Spengler and Toynbee, his name, like that of so many other Russian thinkers, will draw a blank in the West. As far as I can tell, he is not especially talked about in Russia these days, either. But his ideas could not be more relevant. Russian history is cyclical; it may not repeat itself exactly, but it does tend to rhyme. I doubt reading Carlyle, Burke or Proudhon would greatly expand one’s understanding of the political climate of modern England or France; not so with Russia. To make sense of contemporary Russia, you need to go to its 19th-century thinkers. Dostoevsky is not a bad idea, though you will have to stick to his nonfiction, by which I mean The Diary of a Writer. But, as I have written elsewhere, it is too long and shows Dostoevsky at his ugliest. Danilevsky is a much better proposition. He formulated a coherent worldview, and while he may not be talked about, his ideas are alive and well.

Danilevsky identifies eleven civilizational groups (or types, as he calls them): Egyptian, Chinese, ancient Semitic, Indian, Persian, Jewish, Greek, Roman, Arabian, Romano-German, and Slav. Russia and Europe is concerned exclusively with the last two. Ever since Peter the Great’s sweeping reforms grafted Europe on Asiatic soil, Russia has been suffering from something of an identity crisis. The question of how European Russia is, and whether it is European at all, continues to haunt the country, pit Westernizers against traditionalists, and shape Russia’s relationship with its neighbors. For Danilevsky, the answer is obvious and is stated in the very title of the book, which sets Russia apart from Europe. Danilevsky’s Europe can only be considered as a continent in civilizational terms, the geographic ones being entirely arbitrary. An examination of a map of Europe, Danilevsky says, would lead one to conclude that Europe is not a separate continent but only the westernmost peninsula of Asia. What makes it a continent is not some imaginary lines traced by cartographers but its Romano-German civilization, of which Russia was never a part. It did not belong to the Holy Roman Empire, missed the splendor of the Renaissance, and, having adopted Byzantine Christianity, remained completely separate theistically from the Catholicism and Protestantism of Europe. Russia is neither in nor of Europe; it is a civilizational entity unto itself.

A natural scientist by training, Danilevsky compares civilizations to living organisms (much like the thinker Konstantin Leontiev, a contemporary of Danilevsky’s). They germinate, mature, and eventually decay. Like all living organisms, each civilization has a limited life span that does not overlap with the life span of others; the golden age of one civilization will not be concurrent with the golden age of another. The so-called Middle Ages of Christendom may represent a “middle” period of transition for Europe (though even in the case of Europe, it remains a floating concept), but are meaningless in the context of Chinese or Indian history. It is only through the Eurocentric lens of Romano-German civilization that the history of Europe attains universality, and the entire world, with all its civilizations, becomes an extension of Europe. Moreover, it is not just the historical process that is universalized. Inevitably, European civilization is also projected on the rest of the planet; every civilization must Europeanize itself if it is to be a civilization.

Danilevsky attacks the very idea of universality. For him, there is no such thing. Even genius is not universal; at best, it is pan-human — an expression of national genius that appeals to various traits nations have in common. The universalism of European civilization lulls its exponents into the delusion of homogeneity: the idea that the history of man is a story of infinite, unidirectional progress. Danilevsky considers the idea one of the stupidest man could have possibly come up with. Instead of being unidirectional, progress entails historical actors exploring undiscovered avenues to maximize the capital of human experience. Danilevsky doesn’t mind the universality of political systems; what he opposes is civilizational universality, a world dominated by a single civilization. Such a world — promoted by Europeans and Russia’s West-oriented liberals, whom Danilevsky, as a conservative Slavophile, naturally doesn’t like — would preclude variety, diversity, and therefore, any kind of progress; it would betoken, quite literally, the end of history.

As with various species, no civilization can serve as a template for others. Civilizations can influence each other, but copying, or being subjected, to a different civilization invites disaster. Danilevsky sees this in the experience of Czechs and Poles, two Slavic peoples that were forced into Catholicism. The Poles especially — the Teutonic knighthood and aristocracy that were injected into the Polish bloodstream through Catholicism corroded its Slavic democracy by introducing the noxious szlachta and turning the lower strata of Polish society into cattle; the result, according to Danilevsky, was a functioning caricature. If Danilevsky is hard on Poland, his native Russia doesn’t get a break either. If anything, Russia is the most egregious example of a civilizational transfusion gone wrong. Danilevsky has ambivalent feelings about Peter the Great, who, he thinks, both loved and hated Russia. On the one hand, Danilevsky admires the tsar’s administrative acumen; on the other, he blames him for foisting on the Russian people a civilization entirely alien to its soul and essence. The Petrine reforms merely created a civilizational mongrel, a nation with a European head and an Asian body. Most of Russia’s problems stem from its European admixture, a toxic agent that prevents the flourishing of the Russian people and hampers Russia’s pursuit of its glorious destiny.

European (i.e., Romano-German) civilization is Danilevsky’s bogeyman. Like Alexander the Great blocking out the sun for Diogenes, the Europeans always get in the way of Russia’s seeing the light. Danilevsky argues that every ethnic group has a distinctive trait and that the one common to all the Romano-German nations is coercion (the Russian word “nasil’stvennost’”can be translated either as “coercion” or “violence”; nasil’stvennost’ itself is Danilevsky’s translation of the German term “Gewaltsamkeit”). While Danilevsky allows that coercion is not always bad — it enables people to stand up for their rights, among other things — it is conducive to subjugation and domination. The history of European man is a case in point. The religious violence of the Middle Ages, slavery, colonialism, revolutions, the imperialism of the Industrial Revolution — European civilization is a gory canvas of violence and bloodshed.

It is also one of impiousness, a Christianity gone astray. Danilevsky sees both Catholicism and Protestantism as dead ends, the former on account of its caesaropapism, the latter because of its emphasis on the individual relationship that a Christian has with God and its exclusion of all intermediaries. Only Orthodox Christianity has remained faithful to Christian doctrine and its tenets. While it is unsurprising that Danilevsky should accuse the competing Christian branches of impurity — the faithful always believe that salvation is attainable exclusively through their particular vehicle of faith — Danilevsky’s criticism of Protestantism is interesting and deserves a little commentary. His problem with Protestantism is that it leads to the de-Christianization of society. When Christians remove all intermediaries and hierarchies, as Protestants do, Christianity ceases to become public and goes private; as it moves from the public square into private bedrooms, society turns secular. Given that the Protestant countries of northern Europe have the lowest rates of church attendance, wokeism is strongest in Protestant (namely, Anglo-Saxon) countries, and the Orthodox Church is the branch of Christianity that has thus far remained most impervious to such tendencies, Danilevsky may be onto something here. But then Christianity is supranational; Berdyaev, a Russian philosopher I tend to insert into just about every piece of writing these days, rightly found the idea of a Christian state an oxymoron. Christianity is internal and transcendental, not external and material; it has nothing to do with societal institutions. Berdyaev, though Russian Orthodox, was something of an iconoclast, but he would have found the idea of Christianity as a social institution repugnant, nonsensical, and un-Christian. Nor do we need to consult Berdyaev; a Protestant might point out that the secularization of any society is God’s will and is therefore uncontestable.

But Danilevsky believes that a civilization without a religion — above all, the Christian one — is no civilization at all. He juxtaposes the coercive and irreligious Romano-German civilization with pacific and pious Russia. He praises Russia’s peaceful nature, such as it is, but he believes it should be a little less peaceful. In Danilevsky’s analysis, external shocks are the most effective method of state formation; nothing forges a common identity (and a state) like the existence of an enemy. This friend-enemy distinction makes Danilevsky something of a Schmittian — avant la lettre. Danilevsky prophesies a clash between Romano-German civilization (the heir of Rome) and the Slav one (the heir of Byzantium). Such a clash is at once inevitable and desirable. It is inevitable because Europe will never allow Slav civilization to flourish and will continue to make incursions to expand its lebensraum; it is desirable because the civilizational conflict will invigorate and strengthen the Russian state. “The impoverishment of the spirit can only be cured by marshaling and inspiring the spirit, which will mobilize all the layers of Russian society . . . To free [Russia] of its spiritual servitude and slavery, a close union with all the enslaved and imprisoned brethren is necessary; a struggle is necessary . . .” It is a bleak Hegelian vision that gets countries into all sorts of trouble.

Danilevsky has a three-pronged action plan. First, through some laxative, Russia should purge itself of its Europeanness. It is not entirely clear how this is to be attained: a country’s heritage, or any one part of it, is not cargo that can be tossed overboard. Surely one can’t de-Europeanize Russia by replacing violins with balalaikas and ordering that all men start growing beards? Cultural development is an organic process and not one that can be implemented by decree. Danilevsky’s insistence that it must be is in itself quite telling. A strong reaction to something can be an indication of one’s identification with, and so rebellion against, the object under attack. I’ve always wondered if Russian anti-Westerners like Danilevsky — with their solid education and cultural sophistication — would have ever been possible had Peter the Great never opened the window onto Europe. Even Dostoevsky acknowledged the mountain of debt owed to European culture by Russia and observed that Russians were Europeans, though their mission was to renew Europe and save it from its degeneracy (see The Diary of a Writer). I suspect that Danilevsky might have been a lot more European than he was willing to admit, however lush and hirsute his boyar-like beard. But Danilevsky is adamant that Russia must cut the umbilical cord.

Second, it should invade Constantinople. This might sound bizarre today, but the seizure of Istanbul (with its geopolitically vital access to Bosphorus) was an idée fixe for Russia’s 19th-century Slavophiles. In Danilevsky’s thinking, Constantinople (which Slavophiles called Tsargrad — literally, “City of Tsars”) was originally the heart of Byzantium, and since Russia is the heir of Byzantium, it should seize it. That the city has been Turkish for some four centuries and was never Russian to begin with does not faze him. He has concluded that the Turkish Empire has exhausted itself and fulfilled its historical purpose, and so Russia should help itself to some of the territory. To be sure, he does not want Constantinople to become part of Russia since the integration of the “Second Rome” would undermine the Third one (Moscow); rather, it should become the capital and jewel of Slav civilization.

Which takes us to the third item on the agenda. Russia should bring all Slavic peoples together to form a pan-Slavic federation — naturally, under the aegis, tutelage, and leadership of the Russian hegemon. Nor will the federation consist solely of Slavs; Romanians, Greeks, and Hungarians (about the Magyars Danilevsky is almost belittling, calling them a “people-let”) ought to be integrated into the federation as well. Danilevsky has concluded that, just like the Turkish Empire, the Austro-Hungarian behemoth has overstayed its welcome on the historical stage, and Russia should help itself to its non-Germanic population. Russian will be the lingua franca of the federation. Whether all those groups want to find themselves in such a union is irrelevant — as Danilevsky says explicitly, they will not be asked. Russia knows best. That is the leitmotif of the book: Russia is always benevolent, tolerant, and kind, while malevolent, Slavophobic Europe is out to get it.

The best thing that can be said about Russia and Europe is that it’s a curate’s egg. Though interesting and thought-provoking at times, overall this is an exhausting read. Danilevsky is at his most lucid when he sticks to abstract concepts. His criticism of the Eurocentric view of the historical process and his spirited attack on the universalist claims of Western liberalism are certainly on point; recent developments such as attempts to import democracy into the Middle East, and the resistance of various societies around the world to Westernization, confirm the accuracy of his analysis. His treatment of progress is also judicious. Aware of the importance of a metaphysical value system for the health of society, Danilevsky anticipated the changes that the absence of a “moral compass” would engender and the effect that secularization would have on various societal institutions such as that of marriage. While polygamy has not yet received legal imprimatur, as Danilevsky felt it might, modern society has come a long way all the same.

But abstract concepts are not what the book is about. When it comes to the bee in his bonnet — Europe and Russia — Danilevsky goes off the rails. The sanctification of Russia, along with the demonization of Europe, is not grounded in historical facts. While Russian foreign policy was indeed idealistic at times in the 19th century, and the major European powers did apply double standards when dealing with Russia (a tendency that has persisted), the assertion that Russia was never aggressive in its expansion and never started any wars is bunkum. A look at a map of Russian provinces in 1750 and one circa the end of the 18th century will show the fruits of Russia’s annexation efforts, which relied on the sword more than on the cross. Russia subdued the Caucasus through military action; General Ermolov, governor of the Caucasus, unapologetically pursued a scorched-earth policy. Russia also instigated numerous wars, including a series of wars with Turkey in the 18th and 19th centuries. Actually, considering the bellicosity of Danilevsky’s own language, all the talk about peaceable Russia sounds rather odd. As mentioned, Danilevsky believes Russia should incorporate all non-Germanic subjects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and smash Ottoman Turkey. Here he is verbatim: “The principal objective of Russian state policy, which Russia should never renounce, consists of . . . destroying the Ottoman power and the Turkish state itself.” Elsewhere: “A fight with the West is the only cure for the treatment of Russian cultural ailments.”

Calling European civilization coercive, Danilevsky ignores the very coercive practice of serfdom the Russian state applied to its own population. He claims the ultimate tendency of democracy is communism or military despotism, and predicts parliamentary democracies such as England will be hoisted by their own petard; the irony is that while England withstood such pressures, it was Russia that ended up having both communism and despotism. Danilevsky says that, unlike Europeans, Russians have faith in their rulers; that, following the emancipation of the serfs by Alexander II, Russians can be granted all the freedom they desire and can be counted upon not to abuse it; and that Russia is unlikely to ever experience a political upheaval. The Russian Revolution of 1917 gave the lie to all three assumptions. He praises Russia’s imperial court, forgetting that by the time he sat down to write Europe and Russia, the Russian tsars were mostly German and represented the very head of the civilizational mongrel Danilevsky found so unsightly. He treats Romano-German civilization as a homogeneous block; the number of destructive wars between various countries within that fold (the Hundred Years’ War, the Thirty Years’ War, the constant clashes between France and Germany, etc.) suggest it was never the monolith Danilevsky imagined it to be. Nor was the relationship between different Slav peoples of the kind whose season is forever spring (Serbia declared war on Bulgaria in 1885; Bulgaria declared war on Serbia during the First World War; Slav killed Slav during the atrocious Yugoslav Wars in the last decade of the 20th century, etc.).

While he lambasts Europe for its Eurocentric approach to history, his own historicity is highly Russo-centric. The role of Islam in the historical process is confined to the “involuntary and unconscious service it performed for Orthodox Christianity and Slavdom” by protecting the former from the predations of Catholicism and the latter from those of Romano-German civilization. Danilevsky thus reduces Islam, a religion whose wingspan covers territory between Morocco and Indonesia, to a mere “episode” in history, a prop for Slav civilization. Some of the claims are downright risible, as when Danilevsky says that Russia’s implementation of the jury system was not an adoption of a foreign concept but a reinstatement of a Slavic one; he refers to the findings of his fellow Slavophile Khomyakov, who discovered that the Anglo-Saxons, originally a Germanic tribe, must have borrowed the jury system from Slavs back when they were living in close proximity to them; far from an importation, the jury system was a homecoming. Nice try.

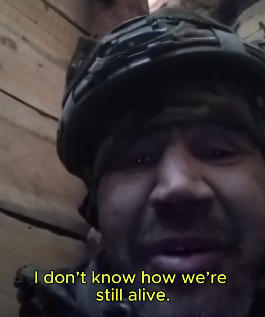

Danilevsky’s ideas are still a part of Russian social, political, and cultural discourse, and though I don’t believe the top echelons of Russia’s political apparatus are motivated by any ideology, they employ these ideas to elicit public support for their state policy. The ideas might have mutated to fit the times, but the “pain points,” so to speak, are the same, as are the blind spots. Like their ideological progenitor, Russians inspired by Danilevsky & Co. have a siege mindset. They believe the West is full of existential hatred for Russia and seeks to destroy it (the US has replaced Europe as the archenemy, though of course Europe hates Russia too). In its objective to obliterate Russia, the West is aided by a fifth column of homegrown liberals forever kowtowing to the West. While I doubt anyone in Russia seriously entertains the idea of taking over Istanbul (or building a pan-Slavic civilization), Ukraine is fair game. According to the imperialist narrative, the Ukrainian people are not a nation but a construct, and their country is part of the Russian ecumene. Ukraine’s present borders are the result of geographic legerdemain performed by the perfidious Gorbachev and garrulous Western parliamentarians — territorial aberrations that Russians, who are moved not by the letter but by the spirit, are only too right to ignore (and besides, as the invasion of Iraq and other military adventures have demonstrated, Western countries themselves ignore international law when it suits them). Liberalism is a racket that boils down to regular (but sham) elections and a McDonald’s in every city; Western ideas of freedom and liberty are legalistic concepts that have nothing to do with true freedom, which can only come from the depths of the soul. The West is putrefying and decaying; if it enjoys superior standards of living, this is only because it is living off dividends paid by its robber-baron past (one of the chapters in Europe and Russia is called “Is Europe Decaying?” — no prizes for figuring out the answer). And so on.

Those who embrace Danilevsky’s vision today like to speak of Russia’s unique historical destiny, its own sui generis path. Taken at face value, this seems like an obvious platitude — the destiny of every country, and certainly of a country as complex as Russia, is unique. What is really meant here is that for Russia to gain its civilizational heights and come into its own, it must break free of the West. This is exactly what Danilevsky wanted. But his discourse contained a glaring paradox Danilevsky either didn’t see or refused to acknowledge: to pursue Slavophile aims, Russia had to be, to some extent, European. Insofar as Russia concerned itself with Slavic nations, many of whom were in Europe (both culturally and geographically), it was bound to remain a European power. Some historians have pointed out that Russia did not release Poland from its grasp in the 19th century precisely because Poland was its gangway into Europe; without Poland, Russia could not be a European power (see Edward Crankshaw’s engaging if tendentious The Shadow of the Winter Palace: “It is not too much to say that it was only by virtue of her mastery of Poland that Russia could feel European”). Russia’s protection of Slavs in the Balkan region was also a function of the same considerations; the Balkan Slavs were its foothold in Europe. If Russia was to lead Slav civilization, then, its destiny was tangled up with that of Europe; breaking free of Europe meant renouncing its pan-Slavist ambitions.

Committed imperialists cannot be bigots if they are to be consistent and, judging by Russia and Europe, Danilevsky was not moved by ethnic or racial questions. Though he imagined a showdown between Russia and Europe, he didn’t call for wanton destruction or violence. All that is to his credit. But pan-Slavism was not just some quixotic ideology. Its effect on Russia was far from benign; the price it exacted, steep. Pan-Slavist sentiment played an important role in pushing Russia into the First World War. Russia did not start the war; it was drawn into it by Austria-Hungary and its Prussian backer. But its involvement in the conflict had strong support domestically, a lot of it from pan-Slavist quarters. The pan-Slavists believed Russians were duty bound to defend their Serbian brothers against Germanic belligerence, whatever the cost. In the end, the cost of plunging into a war it probably did not need turned out to be enormous: tsarist Russia paid with its very existence. Not the end of history, but the end of a history. For those who, guided by grand imperialist visions, support the present direction of Russia’s machtpolitik-driven foreign policy, it is a historical lesson worth revisiting.